I had just finished co-facilitating a workshop at a large Christian conference when a friend approached me to talk about something serious. She referenced the handouts my co-facilitator and I had distributed and pointed to a name in the “great books to read on this subject” page. She let me know that man, one of the writers of the books we referenced who was a well known Christian leader, was a sexual predator, and he particularly preyed on women of color in vulnerable situations.

Before she left, she asked us to share this information with other women cautiously, keeping it under the radar. Her point, she said, was to keep other women of color safe and informed, not to expose herself to the wrath of powerful men. We agreed and removed his name from future handouts, not wanting to promote the work of a man harming women.

And that was the end of our conversation on the subject. It wasn’t until a couple of years later, when news of this man’s predatory behavior broke publicly that the Christian world at large found out what a network of women of color had known for a while. Far from being a poisonous rumor mill, this was a sisterly network of care and protection. Women were cautioned and reminded to pass on the information to those who may need it most.

For much of the time I spent in Christian circles, conservative or otherwise, the above interaction would have been branded as slander or malicious gossip because we were speaking behind a man’s back—it wouldn’t have mattered if the information was true. Women, who are the main targets of admonishments against gossip, would have been silenced and discouraged from passing on such information and quoted some Bible verse about the evils of gossip and idle talk.

I once heard a pastor preach from the pulpit that Jesus charged the woman at the well in John 4 with sharing his message because he knew how much women liked to gossip, and she’d spread the message well. It was said in jest, but it was in poor taste. I suspected he was communicating some of his biases against women.

Chisme or Gossip?

Chisme is the word for gossip in Spanish. As a writer, I find it fascinating that the word chisme in Spanish has a much different connotation from the word gossip in English. “Chisme” denotes something light and communal, generally benign. But “gossip” definitely has only negative connotations--it screams of betrayal and willful harm. In Spanish, chisme can even denote something along the lines of snooping or browsing, like I’m going to go chismosear what’s in that store over there.

Even so, it can be negative in Spanish as well. If a woman gets branded a chismosa, it is not a compliment, just as being known as a gossiper isn’t a compliment in English-speaking circles. I’ve rarely heard men labeled as gossipers even though the research shows that men gossip just as much as women. This is the shadow that patriarchy often casts on the bonds between women. As long as you can frame women’s interactions negatively, you can better control us and keep us from supportive relationships with one another.

However, we can’t deny that not all gossip is harmless. There’s a reason why all the world’s major monotheistic religions have stern admonishments against gossip, rumors, backstabbing, and prying—and they don’t discriminate between true and false information (which is oddly beneficial to those in power). It’s likely we all have an anecdote about the way we’ve seen gossip harm relationships, workplaces, and faith communities.

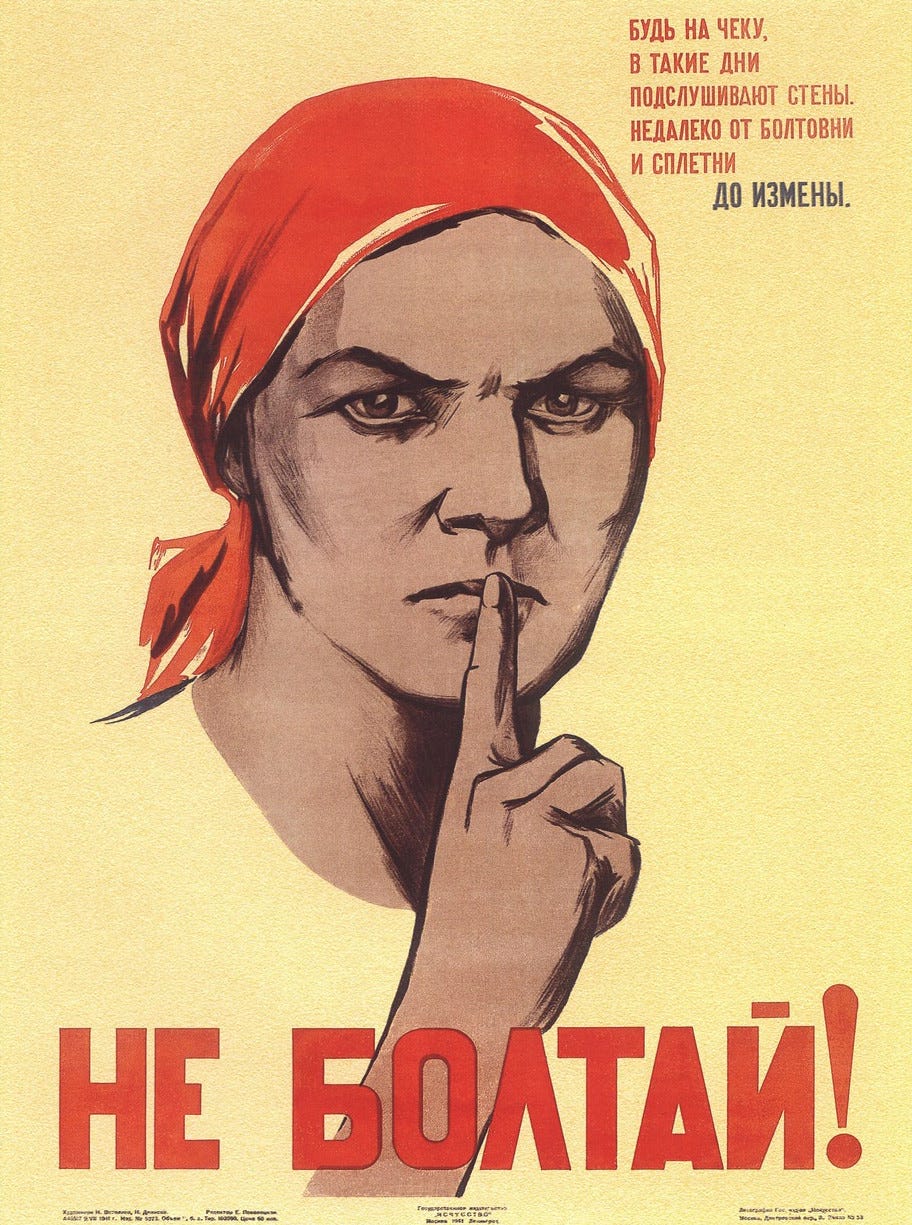

Gossip has also been used by nations to harm, discredit, and even kill human beings. Think of…

the McCarthy witch hunts that could ruin a person and deprive them of their livelihood just by associating them with communism;

the informants during the Soviet era who denounced their neighbors resulting in their being sent to gulags in Siberia literally to be worked to death;

and the methodology used by repressive governments in Argentina and Chile encouraging people to reveal the identities of enemies of the state; these enemies were often “disappeared,” tortured, and murdered.

Gossip is more universal than we would like to admit.

I don’t know anyone that considers being a gossiper anything but a character flaw, and we generally judge those who engage in gossip. Even when we ourselves engage in gossip (and we do), we think negatively of our own selves!

But is all gossip bad?

Can gossip ever be good?

The Grapevine as a Force for Good

I first began wondering whether gossip was always a bad thing a few years ago when I heard a podcast episode of This American Life. The episode discussed the way people in Malawi relied on gossip because there were so many people infected with HIV or AIDS in their country. The grapevine was the only way that people would communicate about who was safe to date or marry, thus protecting themselves and preventing further spread of the virus. Gossip literally saved lives!

And then I remembered the times when, in a work situation, someone had warned me about a particular leader or leaders:

“Don’t cross so-and-so or you won’t advance at this organization. He’s the golden boy around here.”

“Beware of so-and so who says he values women but treats all women with paternalistic condescension.”

“So-and-so thinks he’s not a racist, but makes racist comments all the time and has never hired a person of color for his team.”

In fact, networks of information at work are a great way to be in the know about the implicit values of an organization (these are often in conflict with the stated values posted on the website for the world to see). Work gossip is a way for women and other historically marginalized people to subvert the patriarchal or racial politics of the workplace and survive in a place not designed for our thriving. Of course, the company would rather we did not discuss these things, but we always have to ask ourselves:

who benefits from our silence—those in power or those without it?

One study shows that most of us spend an hour per day gossiping, and we do it in order to make sense of the world we live in—in order to validate our feelings, foster cooperation, and better navigate situations. Far from being negative, gossip can actually be helpful. Only a small percentage of gossip is of the kind we usually think of—the-tear-people-down-out-of-spite-or-envy-kind.

In faith communities where we’re admonished not to gossip, it can be very helpful to know if a leader is inflexible or sexist or a narcissist or a poor communicator. It’s also good to know if the elders have an agenda that doesn’t include LGBTQ+ people in leadership even though the denomination specifically allows for it. I have visited churches because they were affirming of women’s ordination as stated on the website, only to discover that the leadership generally doesn’t support women as pastors or preachers and would never dream of calling a woman to their pulpit. Why is it considered harmful to discuss the clear biases or flaws of leaders and faith communities? This is the gossip we should all share with one another because it would protect us and, in some cases, would save us a lot of heartache.

In a church I belonged to over two decades ago, there was a man in his thirties that only pursued homeschooled adolescent girls as they were finishing high school (so there was not a legal issue to contend with). I commented on his behavior to a Sunday School teacher because I knew it was predatory, but I was shut down and scolded about gossiping.

Wait…shouldn’t behavior like his be talked about?

Shouldn’t the girls (and their parents) be aware of this man’s unsavory predilections?

Again, who is benefitting from silence? Certainly, not these young women.

This is exactly the kind of scenario where gossip would benefit the entire community.

Tricksters for the Common Good

Some of my favorite people in the Hebrew Scriptures are the tricksters. These are usually women who prevail in some way through the use of trickery, cunning, sexuality, and deception. Because they do not have any power or position, trickery is the only way they can subvert oppressive structures and survive.

Some great examples:

Rahab, a Canaanite sex worker, who hides the Hebrew spies in her home (quite possibly also providing them her services), and then lies to the king’s messengers to protect them. The spies likely came to her home because sex workers were privy to all kinds of gossip about the community they were seeking to conquer. Her deceitfulness, in part, results in their success and ensures her survival.

Tamar, the daughter-in-law of the patriarch Judah, pretends to be a sex worker to deceive her father-in-law, tricking him into having sex with her and impregnating her with a son. This is the only way that she can exact justice from Judah, who did not intend to uphold the law by giving his son in marriage to her after she had been widowed by his older son.

Though we are often uncomfortable with their behavior, it’s notable that the Scriptures don’t condemn them, nor are they kept from accomplishing their goals through their deception. In many cases, they are seen as heroic and clever in the sacred text. The one unifying factor in their trickery, however, is that it’s done for their survival and well being in an unjust world. In other words, they never punch down and take advantage of those who are poor or marginalized, but they do punch up to oppressive systems in which they have no voice. Their actions are subversive, for certain, but they are disrupting systems that would seek to deprive them of their rights or deny them life.

On an interesting note, both the sons of Rahab and Tamar end up in the lineage of Jesus.

I don’t believe that people like Tamar, Rahab and the many other tricksters in the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures are being rewarded for bad behavior. Instead, I think we’re being shown that there are times to be shrewd, savvy, and wise.

As long as it’s for good.

What do you think, reader? I struggled to write this but would welcome your thoughts and/or feedback.

Cheers,

Karen

And "Because people think only women gossip, here’s a stock photo of men gossiping" made me giggle with delight. Ha! 😂

Punch up, I really like that!