People of Corn, Missed Connections, and Learning Kaqchikel

Reconnecting to my ancestral roots and letting go of aspirations toward whiteness

Dear friends,

I heard a TikToker talk about colonization once and express bitterly, “…we learned your English, your French, your Spanish, and you learned our…nothing.” I felt that. It’s a visceral truth, and she’s entitled to the bitterness that comes from what might have been, from the grief of all that has been lost.

I confess that I never understood why Americans identified themselves as Irish or German or English when they were clearly just American to me. But I now understand that there’s a longing for missed connections—a longing to know and learn about where we come from and who our ancestors were.

The TikToker made me think about the indigenous language I might have spoken had Guatemala never been colonized. I was thinking a lot about indigenous wisdom at the time because I was reading Robin Wall Kimmerer’s beautiful book Braiding Sweetgrass (stop what you’re doing and go get this book from the library right now!) Kimmerer speaks with candor about the challenging process of learning the language of her own North American indigenous family, and she inspired me with the knowledge that it is never too late—our ancestors’ languages and wisdom can be recovered.

Learning Kaqchikel

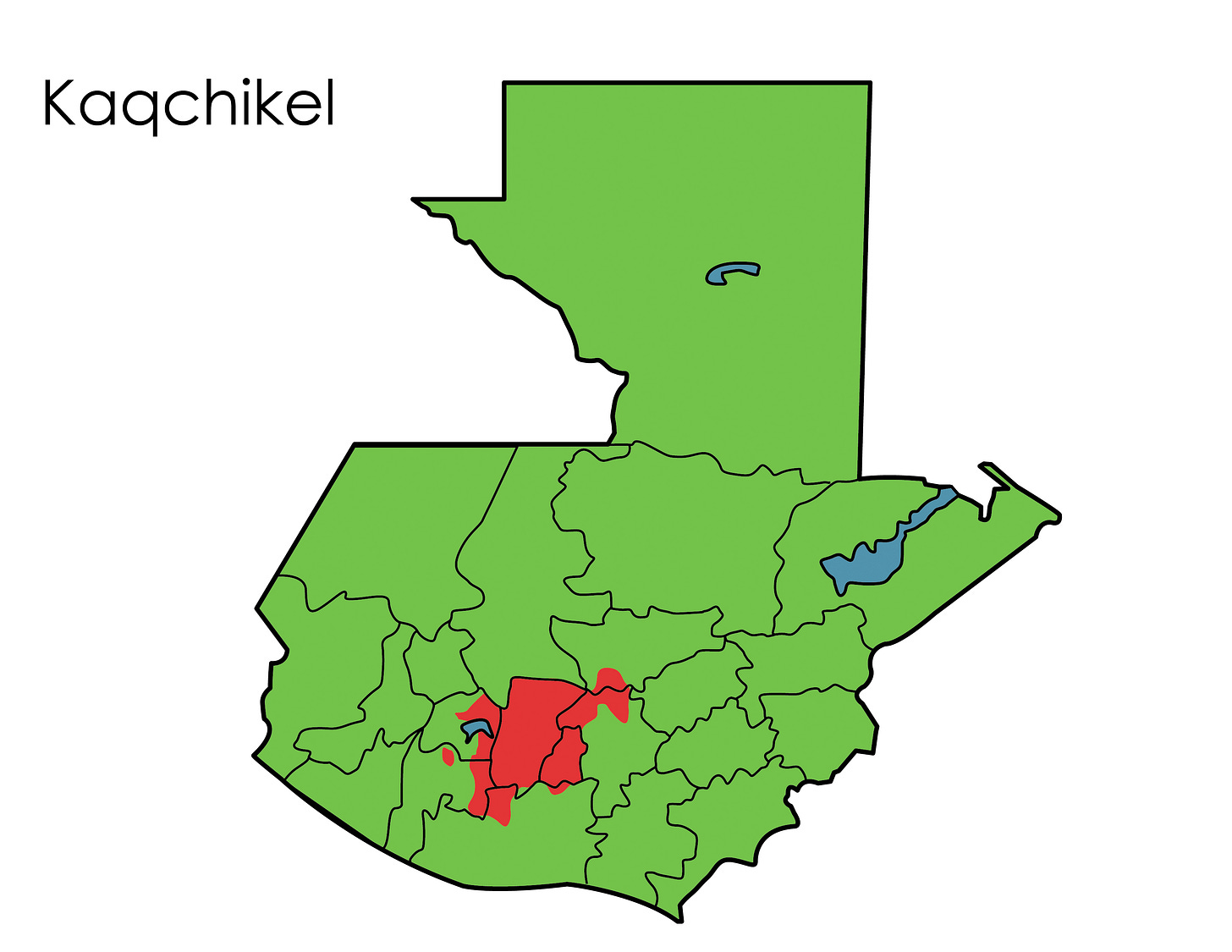

So last summer when I was celebrating my 50th birthday in Guatemala, I took language lessons in Kaqchikel,1 the most widely spoken Mayan indigenous language in the region where my father was raised in Guatemala, the department of Sacatepéquez, located just to the west and south of Guatemala City.

I’m calling it a language, which it is and always has been, but my family never referred to it that way. To them it was always one of many “lenguas (literally, tongues) or dialects.” It was always spoken of negatively, in a way that was meant to convey that it wasn’t as sophisticated as Spanish, wasn’t worthy of rigorous study, like my boring Spanish grammar classes that explained the subjunctive tense and the rules for the accent mark. You would no more study Kaqchikel than you would study Pig Latin. I heard the message loud and clear: this “dialect” is inferior…and, by extension, so were the people who spoke it.

I know it sounds like I’m being very hard on my family, but this is a message that has been prevalent in Guatemala for generations, ever since the first Spanish conquistador arrived and wrongly placed himself at the top of the hierarchy of what it means to be human. In the 1930’s, a Guatemalan president said publicly that the country would never get ahead while there were so many “ignorant indians” among us and encouraged migration from Europe to “improve the race.”

It was not hard to absorb all the aspirations toward whiteness in my family and in my Guatemalan culture. For many people, aligning themselves with whiteness wasn’t just a preference but a matter of survival—life is easier for white Guatemalans; they have access to better opportunities, don’t suffer exclusion, and they’ve never suffered the threat of extermination by the government.

I write in my book: “I understand now that my family did not know how to disrupt the harmful systems that create hierarchies, that divide us by race….” So they did the only thing they knew to do: they taught us how to adapt and work within them for our own well being. I don’t blame them. Even if you’re a brown or other person of color, you can’t swim in white supremacist waters all of your life without swallowing that toxic water. At the same time I knew they would not understand my desire to learn Kaqchikel now. But learning and valuing this language is one way for me to disrupt and not assimilate to oppressive systems. After all, those who belong to the kin-dom,2 use their resources and privileges to build a better and more just society.

The People of Corn

I’ve always had a gift for learning languages. I don’t say that pridefully because it truly is just a gift and not something I’ve had to work very hard to achieve. The combination of an extroverted personality, a good ear, and an obsessive desire to communicate created the perfect conditions for me to be a good language-learner.

And I’m happy to report that the trend continued with Kaqchikel. One of the truisms of language-learning is that when you learn a language you also absorb a lot of the culture. One of the many things I learned about Mayan culture is that it was very closely tied to the land, and to corn, in particular. In fact, they refer to the land where they live not as Guatemala (which means land of many trees in Nahuatl) but as Iximulew (pronounced ee-shee-moo-lev), the land of corn.

In the Mayans’ sacred book the Popol Vuh, the creation myth says that two gods created humans out of corn; our bodies and bones are made of corn masa. Corn, like people, comes in all different colors. In gratitude to the gods for this gesture, humans learned to work the land and give it life by planting corn. It’s a reciprocal relationship: the people are made of corn, and they cultivate corn.

I couldn't help but wonder what it must be like for the indigenous Mayans to see everything, not just their land, renamed with Spanish or other foreign terms. My teacher is from a town in the mountains called Junapju, named after a Mayan God. But everyone in Guatemala knows this town as Santa María de Jesús, named literally Holy Mary of Jesus. He taught me the names of so many towns that I already knew but with Spanish names.

What the Spanish colonizers did is akin to someone walking into your house and deciding that your name is now Susan; renaming everything inside it for their own convenience; and then throwing you out!

They never considered learning from the indigenous Mayans. Even though the Mayans had their own sophisticated numbering system that included a zero, a number they discovered independently of the Sumerians. They successfully used cacao beans as currency and ran a robust economy. They revered the land and agriculture, giving them a sacred quality and planting according to the phases of the moon. And they had not one but at least seven sacred books (a Spanish priest destroyed several of them).

In fact, many Guatemalans today revere the ancient Mayans while denying that the indigenous people living today in Guatemala are also Mayans.

And so, dear readers, I am re-learning what was lost before I was even born. I only study on Saturdays now, but I’m creating space every week to reconnect with my ancestors and their sacred knowledge. There’s a fine line between appreciation and appropriation, and I’m working hard to stay on the appreciation side because, while I have indigenous blood, I’ve never experienced the marginalization that comes with an indigenous identity.

I don’t know who to credit with this quote but it’s a beautiful truth:

“I feel my ancestors in my blood. I am a body of people that are asking not to be forgotten.”

Want to learn to say hello in Kaqchikel? Watch this 28-second video and don’t forget to listen and repeat:

So what are you learning? How are you connecting with your roots? I’d love to know and continue the conversation. I could talk about this all day!

Cheers,

kg

Note that there are various spellings of Kaqchikel since the word is translated.

Biblical scholar Ada-María Isasi Díaz imagines the community of God not as a hierarchical monarchy with kings at the top and peasants at the bottom but as a kin-dom, more like the parable of the banquet where all are invited and share the same table as equals. Her kin-dom is a more personal vision that blends the ideas of flourishing, or abundant life, with family.

So good!! I follow a couple of indigenous leaders who teach Nahuatl. I too would love to know the indigenous roots of my ancestors. Thank you for sharing your journey with us.

I love this so much!!!! Thank you for sharing!